For a while, there, the prosecuting attorney hadn’t yet emailed me back, and the sheriff hadn’t yet shown up with a warrant for my arrest, so my fate was pretty much in limbo. I was a bit anxious.

But let me explain.

After Christmas break, in response to a gang “beat-in” that happened in my school in November, my school’s faculty gathered for a gang awareness training. The four members of the area’s gang-fighting police task force had come to show us pictures of local tagging, drawings to look for, and patterns of behavior to note. Watching the presenting officer pace like a caged tiger was unnerving, but the content of his lecture was even more so.

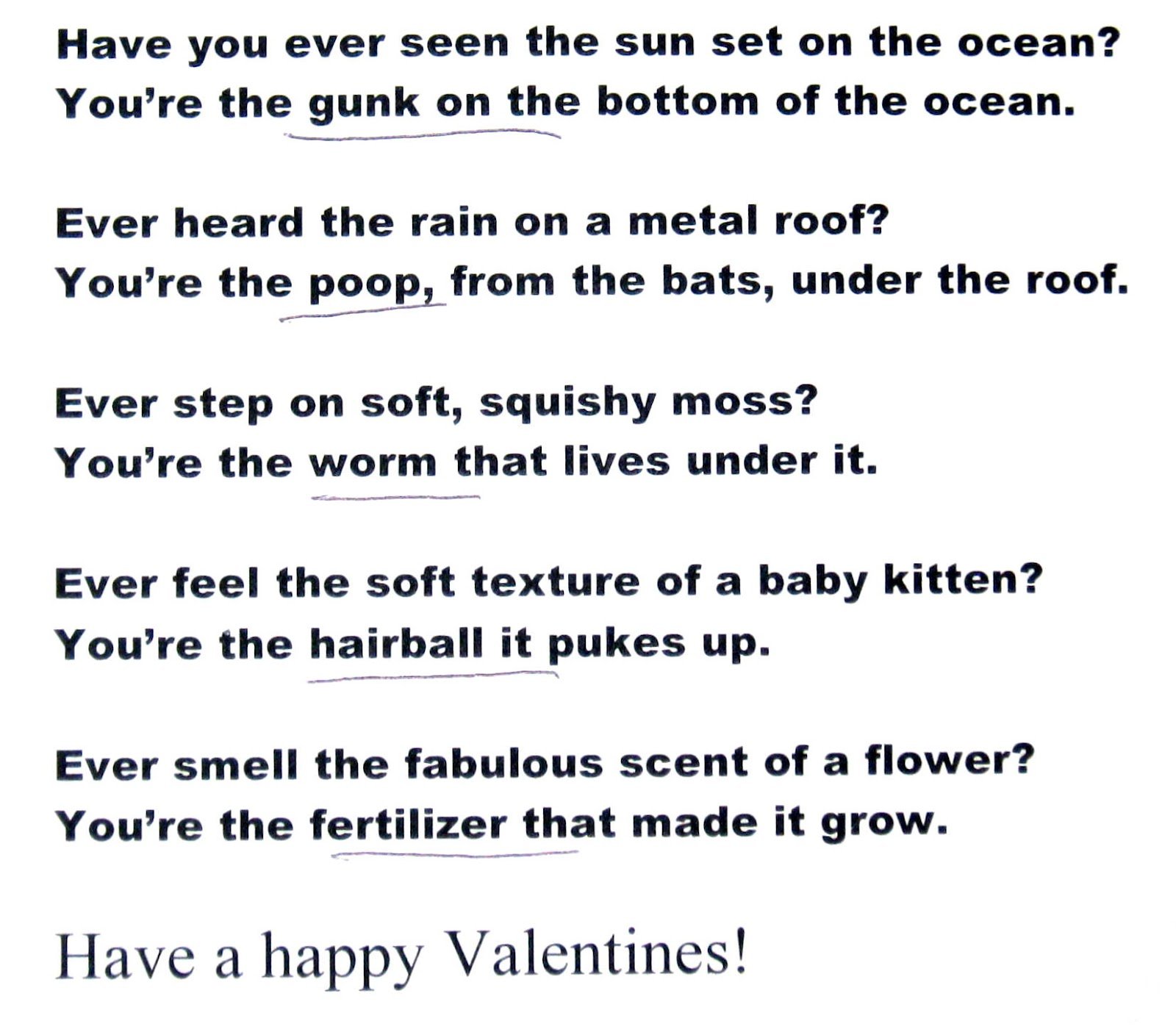

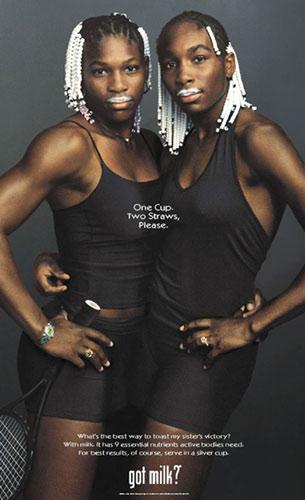

He showed us how gang signs make it into mainstream media, like in this photo (note the hand “c”):

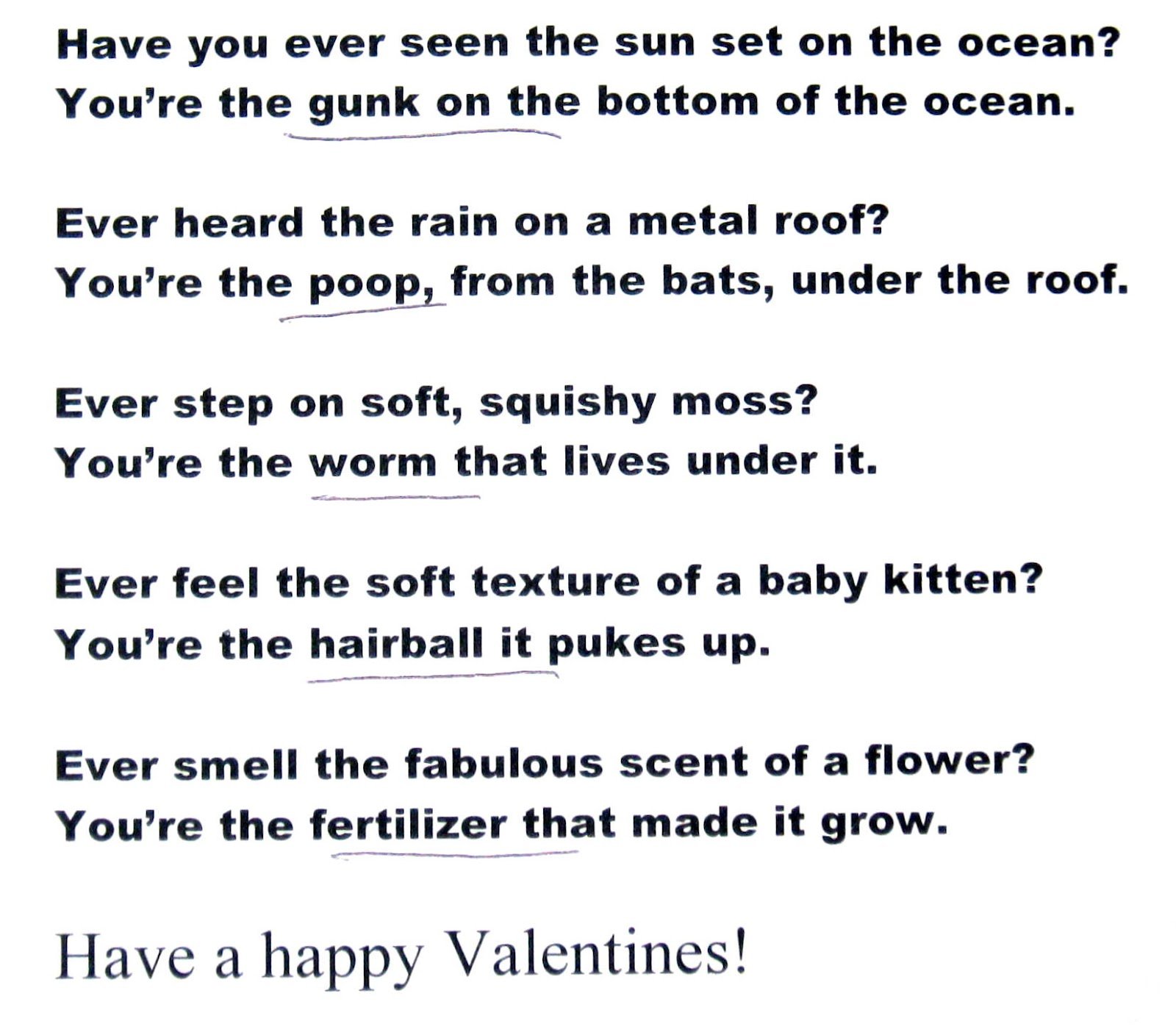

(And later, feeling all sleuthy, I found a Sureños hand sign on this album featured on NPR.)

Of course we saw pictures of gangsters displaying their guns and showing them off to very young children, too, and video of a real beat-in. It was sickening stuff, for sure; one teacher commented to me later that gangs are “pure evil.”

“Yes,” I said. “But at least it’s obviously so.”

I don’t know that he caught the nuance of my take on evil; I’m sometimes so caught up my own failings that I don’t have time (or occasion, thank goodness) to worry about gangs.

Not that they haven’t been on my mind since back in in the fall, when my school made local news headlines after a twelve-year-old boy was arrested for leading the alleged beat-in.

“Fears of gang violence are at an all-time high,” one TV reporter had said in her coverage of the news, a statement way overblown if not entirely untrue. Shucks, I am the teacher who broke up the beat-in, which had happened in the bathroom across the hall from my classroom: “Boys, stop–and go to class.” In fact, I hadn’t even known what I’d interrupted was even related to the much-publicized gang incident until a week or two later, when I received a subpoena to testify against the arrested, alleged beat-in leader.

I headed off to the court lobby on the appointed day and read from David Copperfield until the gang task force came out and told me the case had been continued, and then I went on my merry way to Lowe’s.

As I drove down a one-way street through town, I saw a boy wearing ear buds approaching on his bike from an alley. I guess he knew he was crossing a one-way street, so he only looked for cars in one direction, but it was the wrong direction. I slowed when I first saw him and easily stopped before we would have collided, but when he saw me he started and then mouthed, “Sorry.”

I would’ve hated to end a young person’s pleasant ride, even if the crash and burn would have been mainly his fault.

A month later, I again entered the courthouse. Would I even be called to testify? Should I be nervous? I’d testified in custody hearings before, summonsed by parents who believed that if I agreed that their child was not doing his homework, he’d be better off changing homes. The most recent time was the most embarrassing: not until I was actually testifying did it occur to me that it would have been a good idea to review my parent contact notes. All I could say when the attorney asked me if “Mom but not Dad” was in frequent contact about school work was, “Well, I’m not sure. Maybe.” How incompetent that made me feel!

For this gang beat-in trial, like all of the other times I’d been called to testify, I had been prepped in no way, other than when I introduced myself to the prosecuting attorney, who asked if I’d heard the boys say anything about gangs when I broke up the fight. I knew my answer to that question–No–but mainly my recollection about what I’d seen was not very clear. I decided that I would testify based on my initial beliefs regarding what I’d seen, that the accused and another boy were both throwing punches at the victim, even though I’d heard from the principal the next day that the arrested boy had claimed he was not the one punching.

It’s probably a documented dilemma for a witness in court: my desire to be definitively helpful outweighed any personal acceptance of the fuzziness and indecipherability of my memory, and when I was asked if any of the accused boy’s punches had landed on the victim, I said I believed so, yes.

I was soon excused and found myself driving down the same one-way street again on my way to drop off some tools at a friend’s house. However, I was so distracted by fear that I had mis-testified–I realized suddenly that I couldn’t have seen any of the accused boy’s punches land: I was behind him as I’d entered the bathroom–that when I reached the stop sign at the end of the street, I very nearly pulled out in front of another car. Assuming that the cross street was also one-way, I’d forgotten to look both ways.

Of greater concern to me was that I maybe had mis-influenced the accused boy’s destiny. In my state’s criminal laws regarding gangsters, just being a member in a gang is not illegal. However, committing any sort of crime–like a beat-in–in the name of the gang means that a gang member can be charged not only for the beat-in, which would likely be classified as a misdemeanor, but also for a felony of gang participation. In short, if the accused boy did not actually land any punches on the victim, that would perhaps spare him a conviction of assault which, more importantly, might mean he would also avoid being tagged a felon.

I knew what I had to do: I went back to the courtroom. Luckily for me, just leaving the courthouse was a member of the gang task force.

“What happens if I need to amend my testimony?” I asked him. We headed back up the the courtroom, and while he entered to convey my testimonial adjustment, I continued reading Dickens; soon he came out and told me I was again excused.

But I still didn’t rest easy. How could I be sure that the gang task force officer accurately conveyed my message to the right people? How was I to know that I hadn’t totally ticked off the judge and prosecuting attorney wasn’t now on the “Most-Wanted Perjurers” top ten list?

To make matters worse, I was about to begin a term of jury duty: Would I find myself on the jury in my own perjury trial?

There was only one way to find out: put my confession in writing. The next day I emailed the prosecutor to “clarify” my realized mis-testimony. It wasn’t until the next day, though, many hand wringings later, that I received a thoughtful, gracious, and detailed reply that alleviated all of my fears of the student’s unfounded conviction and my arrest for perjury.

As for the student, barring other pending court actions against him (I’ve heard there are things in the works, but I don’t know anything about them), it’s not entirely impossible that he’ll be returning to my school, since the gang charges in this case were dismissed. If indeed he is now clear, he awaited trial in juvenile detention for two months without founded cause.

That would be a crime.