Fam

Neither of us had prepared for an only five-hours-start-to-finish labor:

And giving birth on the deck in the presence of the dog (and barely in the presence in the midwife, who’d only arrived eight minutes before) wasn’t what M (pictured) had in mind, either:

Tonight as I held H while M read bedtime stories to N, I wondered, “Is there anything M wouldn’t be able to do?”

The reporting of oddball incidents of random violence at remote recreational hot spots sometimes feeds my own general wariness when it comes to strangers’ potential propensities to do terrible things, leaving me feeling unnecessarily insecure. But I don’t think that means I’m completely wacko all of the time.

Take our recent trip to the local swimming hole. It’s a federal place, national forest or something, but in the middle of nowhere and out of reach of cell service and everything else. The water is cold and refreshing, and deep enough that I wasn’t too worried that the apparently local young man in orange shorts who was climbing the cliff and then up a tree on the cliff and then jumping off would hit bottom (his head on the cliffs, well…).

“It was four feet deeper earlier this month,” he told me as he climbed and as I kept N from sliding down the shifty gravel into the depths. His feet smacked the water.

M and I took turns taking leisurely swims for the length of the hole, and then we found a shady spot along a calm inlet and ate our pasta salad picnic.

Soon I noticed that Mr. Orange Shorts and his buddies, plus two other guys who’d been hanging out, weren’t swimming any more, but were back at the parking area with a bunch of other guys who’d showed up in their pickup trucks. One truck had driven by the hole, paused while the driver stared down on the scene, and sped in reverse back to the others, where he sat with the others, taking long glances toward the swimming hole–not at us, but at the mixed-race group that had shown up soon after we’d gotten there and were lounging, laughing, and swimming.

I was feeling nervous, and wondered if we should call law enforcement to disburse the racial hatred I sensed in the white locals’ clustered, unswimming stares. It made me a bit tense and eager to leave, and as we walked to the car past the trash cans, Mr. Orange Shorts, who was throwing away a beer case, said to me, “I’m scared.”

Scared of what? I thought (rather cluelessly). Too much cliff diving? Out loud I gave a polite chuckle.

He continued, “Did you see that woman?”

Oh. There had in fact been a black woman swimming in the water.

I didn’t say anything more, and breathed a sigh of relief we’d made it to the main road. It was soberingly astonishing, the local festering of racial hatred.

Side note: I was again taken aback when, several weeks later, I heard in an interview on Fresh Air about the ongoing existence of slavery, in the U.S. tomato industry.

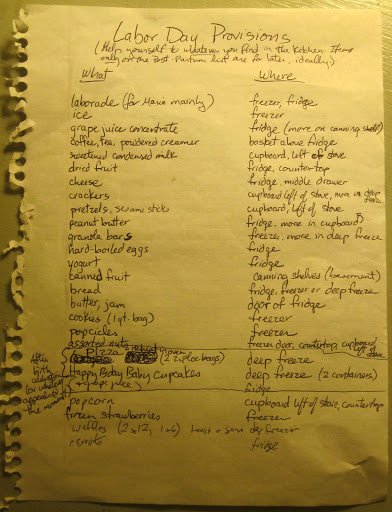

The due date has come and gone, the house, basement, and shed are in order, the freezer’s full of food, and we’re so confident in the perpetuity of our waiting that on Tuesday I even scheduled an eye doctor appointment for yesterday (after I built a monument to M with blocks).

The baby and its parents also gave N a present on Wednesday evening. On Thursday morning when I got out of bed she was no longer in hers; I found her outside.

Solomon was wise not because he identified the correct biological mother but because he made apparent which woman was fit to parent.

The story of Jesus calming the storm (Mark 4:35-41) is often used as a textual basis for “Do not fear, God is here” type pastoral lessons, but that idea, that God is out there looking out for The Fellowship, bugs me at times.

Take that Psalty song “Say to the Lord ‘I Love You’” on one of N’s tapes, in which children talk about their love for God. N has taken to reciting these anecdotes, including the one I find most appalling: After looking so hard for a lost baseball, a boy closes his eyes to pray. When he opens his eyes, there is the baseball, at his feet. “I love you, Lord,” he says fawningly. How unfair for Psalty’s child listeners to be taught to expect that kind of guardianship!

While I’m not sure what exactly it is that the Mark story does teach, it seems to me that its message might not be about casting all our cares upon Jesus. In fact, in a way it teaches the opposite, since after the disciples wake up (pray to) Jesus to tell him of their plight, he scolds them: “Where’s your faith?” he asks. I wonder if he followed that with, “In me? Jeesh, I hope not!”

Now, of course the disciples got what they wanted—the wind and waves were calmed—and presumably their question “Teacher, don’t you care if we drown?” was answered with decisive divine intervention.

But they also got a tongue lashing? So, then, in whom exactly are they to have faith, if not Jesus? The problem-solving power of group thinking? Positive outlooks even in the face of adversity, in this case thinking about their boat more as half empty than half full?

I don’t have answers to these questions, but today’s NPR story about a hate-crime victim fighting for his attacker’s life is a storm-calming testimony.

Author’s note: A college prof once told my class that it’s better to be honest than good; my brother’s wise idea for this blog’s title suggests that both my better and lesser points are, after all, me.

Up until this week I tried polite diplomacy.

Here’s the back story: The cattle owned by the Land Renter (LR) who is renting the farmland on three sides of our property have escaped onto our land many times. When I’ve called him he has always come to herd them away and presented feeble fix-it attempts; on one occasion he rather bluntly pointed out that the “first problem” to deal with were the tree saplings we’d planted apparently too close to the fence (maybe an issue five or ten years down the road). He also said that the cattle-trodden fence sections on the Western Landowner’s side wouldn’t be a problem, since they didn’t have cattle there now, anyway.

I also called the very apologetic Eastern Landowner, and we exchanged assurances that he would replace the fence at his expense (since we’re not using it) and we would be moving our saplings farther from the fence line to prevent any future problems.

When I called the Western Landowner, she merely said she’d look at the fence; a few days later we did in fact see her car slow while driving by.

And then this week:

On Monday, LR’s high-school just-graduated son herded their heifers into the above-mentioned Western Landowner’s section of pasture directly adjacent to our garden and separated from our land by a flimsy fence with at least two unrepaired sections that the cattle have crossed a number of times before. I was napping at the time, and watched foggily from my bed as the herd stampeded into their new domain. I jerked myself awake in time to run out to flag down the son just as he rode his four-wheeler over to the fence.

“There are several bad sections of fence along here,” I said, pointing them out to him.

“I was just coming to check them,” he said.

“I think the cattle have gotten out down here, too,” I said of one place where the fence was stretched and bunched down.

“Have you seen them get out there?” he demanded. “It looks to me like they just pushed against it there.”

“No, I didn’t see that. But it needs to be fixed. These sections need to be fixed before your cattle are in here.”

He got off at the uppermost broken spot, and with his bare hands pulled and twisted together some of the severely damaged woven wire, and then got back on his four wheeler and looked at me.

I looked at the twisted wires, and then at him. “I’m not convinced.”

“I don’t think they’ll get out,” he said.

That’s when I decided that what my mom would later wonder about is right: some people don’t understand the language of courteous neighborliness. I had a miniature explosion.

“You’re telling me that we have to be concerned about our garden—which we put a lot of hard work into—because you run shitty fences. That’s ridiculous and unacceptable.”

He turned sulky and said, “We can put the gates [which he’d used to patch the Eastern Landowner’s side’s vulnerabilities] over these spots. Can we cross your land to do that or do we have to drive all around your property get them?”

“Thank you for asking permission to cross my land,” I said. “Let’s do it now; I’ll help you.” We talked about his and his brother’s schooling while we worked, and ended on good terms albeit with a customarily feebly fixed fence.

My only regret was that I’d said the “shitty” line to him and not to his dad.

Then.

Yesterday we went to visit my parents, and I worried we’d come home today to trodden vegetables. My spirits lifted, though, when we came back to see that all the heifers were in their confines and our garden was as we’d left it—in need of potato bug collection, which we hopped right on.

As we finished up picking the bugs and weeding the onions, a man I’d never met before stopped in to ask if we plan to use the pile of rocks in our pasture (we do). As I talked with him, M, still down at the garden, called for me—a heifer had just then jumped yet another section of fence and was munching our corn.

I ran inside for some leather work gloves and the rope I’d made handy after Monday’s relocation. The man seemed willing to help us, so I said, “I don’t want to chase it back across the fence—I want to catch it.”

We tried and tried to corner it and rope it (“You should take lasso lessons,” he said) until finally with our dear dog’s, M’s, the man’s and my coordination, we corralled it in between our two woodpiles facing what I thought was an impermeable section of fence and blocked behind with a pallet tied to some other fence posts.

I started making phone calls, first to my brother-in-law: “Do you know anyone with a cattle trailer we can borrow?” He didn’t, but suggested I try a neighbor down the road. They didn’t answer the phone.

I called another neighbor; they didn’t have a trailer.

Meanwhile, the cow in the makeshift stall was denting the metal trash can of kindling I keep there and occasionally backing towards me as I leaned against the pallet, poking her with a pointy stick when she pushed against the pallet.

I called the man at church who’d first told me about my right to corral and hold for ransom—or even sell to recover costs—trespassing cattle, but he didn’t have a trailer either.

“Look in the newspaper under the livestock section,” he suggested. “There are usually cattle buyers listed there.”

I called my brother-in-law back to see if he had a newspaper. He did, but there were no cattle buyers listed as such.

“Oh, hey, there’s this guy,” he said, reading aloud the name of someone who sounded like he would maybe be able to slip on over and take away the penned heifer. But just as he read the name to me, the cow tried to jump—and smashed to the ground—that “impermeable” fence (and a portion of our woodpile) and moseyed off, eating the grass along our driveway (which goes through the Western Landowner’s land).

“Oh, great,” I said, my heart sinking. “Can you come help me catch it again?” But no—the heifer wasn’t on our land anymore, so it wasn’t fair game.

Boy, was I disappointed.

I called the farmer. Busy. I called the Western Landowner. Busy. I put my gloves and rope away. I called the farmer’s cell phone.

“Hi, LR. You’ve got another section of fence that needs to be fixed; we just chased a heifer out of our garden. It was eating our corn and potatoes, and this is ridiculous.”

“We’ll be right over,” he said.

I called the Western Landowner, and after she tried to say the fence was LR’s responsibility but we couldn’t expect him to fix it, and she couldn’t fix it, I told her that I would not pay for damage to the fence caused by the cattle on her land. She said she’d come by and look at the fence on Saturday.

I drank a glass of water.

LR and his two boys showed up and herded the remaining cattle into the barn lot. I approached them; he said nothing to me.

A moment of quiet passed, and then I started.

“I am really offended,” I said. “You have never once apologized to us for the damage your cattle have caused and for the inconvenience this has been for us. We work hard in our gardens, and we’re not going to tolerate your cattle destroying our crops because you keep crappy fences. I’m extremely frustrated.”

“Let’s go see your garden,” he said.

The damage, while apparent, didn’t look like much. “Your heifer went out through the woodpiles up there, too, and knocked down that fence,” I said. “This is just unacceptable and you need to take responsibility.”

“Now wait a minute,” he said. “I’ve been blasted twice now, and I haven’t even had a chance to speak.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m listening.”

“How much do you think this damage is worth?” he asked, pulling out his wallet.

“This damage is nothing,” I said. “But the rest of the herd could have been right behind this heifer when she escaped, and the potential for a lot more damage is what I’m worried about. We’re lucky we were home—we’d been away since yesterday. You are responsible for your cattle, and you need to fix the fences so they don’t get out.”

He pulled out fifty dollars. “I hear you,” he said. “Here. Take it and buy yourself some corn cobs. I want to keep happy neighbors.”

“I don’t want to be paid for this damage; it’s nothing,” I said. “I forgive you. I don’t want to be paid.”

I started crying. “I forgive you. I just want the fences fixed.”

“Take this,” he said. “We’ll stretch more barbed wire tomorrow, and I’ll go buy a new fencer and put up a powerful electric fence that they will not get through.”

“No,” I said. “Use the money for your materials. This damage isn’t worth it.”

“You’re offended, and I’m offering you this,” he said, tossing the bills into the corn patch.

I don’t remember how the other details fit in, but I remember pointing out that we’re of the same denomination (“I’m Christian,” he clarified. “Well, I am, too,” I said) and asking him if I could give him a hug.

“No,” he said, extending his hand (I shook it). I’m not sure, but I think when I was tearily refusing the money and forgiving him I’d also put my hand on and squeezed his shoulder several times.

“We’ll be over tomorrow morning to fix that fence. After I fix up the new electric fencer, they will not get through. They won’t touch that fence twice.”

At that point I remembered I’d wanted to ask him why I feel the current electric fence pulsing in the heating pipes in our house (when I’m barefoot and touch them); that provided some comic relief.

“This new wire will be hot,” he said. “Like we have around our house,” he said knowingly to his sons.

“Could you put it a few feet back from the wire fence?” I asked. “I have a small daughter.”

“She won’t touch it twice,” he said.

Believe me, I’m going to be checking out that wiring—and our heating pipes—after they’re done working. There are laws about appropriately unregulated current in fences.

And I just may be making a fifty dollar contribution to Heifer International—in LR’s honor.