Not long ago M, my brother, and I started a consulting “business.” Really, it’s just a website offering the world a chance to pay us to do the things we enjoy, and we haven’t really begun advertising it, yet, and we’ve so far had no clients, so it’s nothing too spectacular.

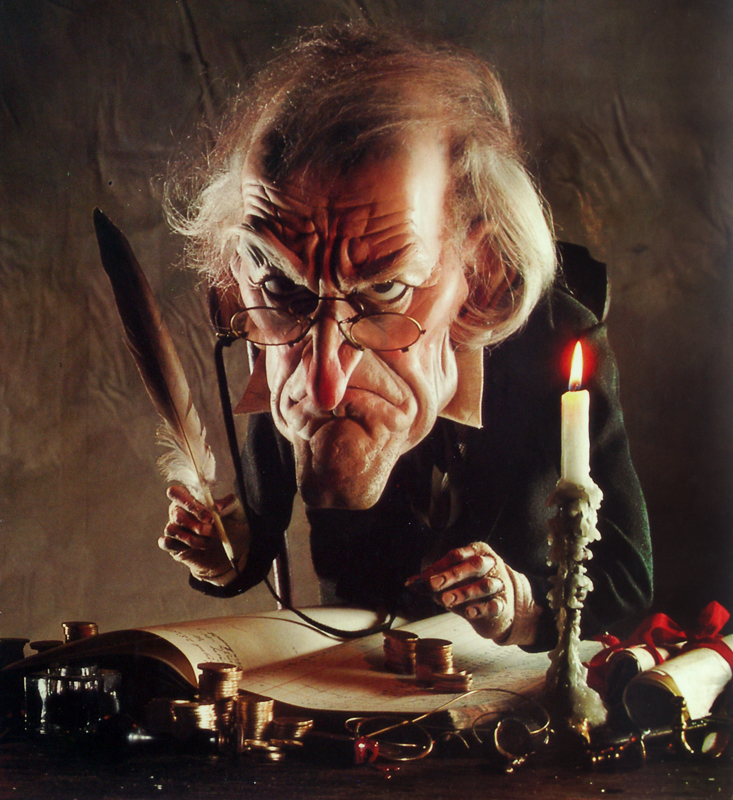

However, the idea is rather Dickensonian, as I read in David Copperfield yesterday. The Micawber couple are definitely my favorite characters in the book, always down on their luck. Sometimes they are accordingly in the throes of despair, but more often they are jovially awaiting an elusive but ever-nearing incoming ship.

Here’s where I found myself, yesterday, in Mr. Micawber, as described by Mrs. Micawber:

‘As we are quite confidential here, Mr. Copperfield,’ said Mrs. Micawber, sipping her punch, ‘Mr. Traddles being a part of our domesticity, I should much like to have your opinion on Mr. Micawber’s prospects. For corn,’ said Mrs. Micawber argumentatively, ‘as I have repeatedly said to Mr. Micawber, may be gentlemanly, but it is not remunerative. Commission to the extent of two and ninepence in a fortnight cannot, however limited our ideas, be considered remunerative.’

We were all agreed upon that.

‘Then,’ said Mrs. Micawber, who prided herself on taking a clear view of things, and keeping Mr. Micawber straight by her woman’s wisdom, when he might otherwise go a little crooked, ‘then I ask myself this question. If corn is not to be relied upon, what is? Are coals to be relied upon? Not at all. We have turned our attention to that experiment, on the suggestion of my family, and we find it fallacious.’

Mr. Micawber, leaning back in his chair with his hands in his pockets, eyed us aside, and nodded his head, as much as to say that the case was very clearly put.

‘The articles of corn and coals,’ said Mrs. Micawber, still more argumentatively, ‘being equally out of the question, Mr. Copperfield, I naturally look round the world, and say, “What is there in which a person of Mr. Micawber’s talent is likely to succeed?” And I exclude the doing anything on commission, because commission is not a certainty. What is best suited to a person of Mr. Micawber’s peculiar temperament is, I am convinced, a certainty.’

Traddles and I both expressed, by a feeling murmur, that this great discovery was no doubt true of Mr. Micawber, and that it did him much credit.

‘I will not conceal from you, my dear Mr. Copperfield,’ said Mrs. Micawber, ‘that I have long felt the Brewing business to be particularly adapted to Mr. Micawber. Look at Barclay and Perkins! Look at Truman, Hanbury, and Buxton! It is on that extensive footing that Mr. Micawber, I know from my own knowledge of him, is calculated to shine; and the profits, I am told, are e-NOR-MOUS! But if Mr. Micawber cannot get into those firms–which decline to answer his letters, when he offers his services even in an inferior capacity–what is the use of dwelling upon that idea? None. I may have a conviction that Mr. Micawber’s manners–‘

‘Hem! Really, my dear,’ interposed Mr. Micawber.

‘My love, be silent,’ said Mrs. Micawber, laying her brown glove on his hand. ‘I may have a conviction, Mr. Copperfield, that Mr. Micawber’s manners peculiarly qualify him for the Banking business. I may argue within myself, that if I had a deposit at a banking-house, the manners of Mr. Micawber, as representing that banking-house, would inspire confidence, and must extend the connexion. But if the various banking-houses refuse to avail themselves of Mr. Micawber’s abilities, or receive the offer of them with contumely, what is the use of dwelling upon that idea? None. As to originating a banking-business, I may know that there are members of my family who, if they chose to place their money in Mr. Micawber’s hands, might found an establishment of that description. But if they do not choose to place their money in Mr. Micawber’s hands–which they don’t–what is the use of that? Again I contend that we are no farther advanced than we were before.’

I shook my head, and said, ‘Not a bit.’ Traddles also shook his head, and said, ‘Not a bit.’

‘What do I deduce from this?’ Mrs. Micawber went on to say, still with the same air of putting a case lucidly. ‘What is the conclusion, my dear Mr. Copperfield, to which I am irresistibly brought? Am I wrong in saying, it is clear that we must live?’

I answered ‘Not at all!’ and Traddles answered ‘Not at all!’ and I found myself afterwards sagely adding, alone, that a person must either live or die.

‘Just so,’ returned Mrs. Micawber, ‘It is precisely that. And the fact is, my dear Mr. Copperfield, that we can not live without something widely different from existing circumstances shortly turning up. Now I am convinced, myself, and this I have pointed out to Mr. Micawber several times of late, that things cannot be expected to turn up of themselves. We must, in a measure, assist to turn them up. I may be wrong, but I have formed that opinion.’

Both Traddles and I applauded it highly.

‘Very well,’ said Mrs. Micawber. ‘Then what do I recommend? Here is Mr. Micawber with a variety of qualifications–with great talent–‘

‘Really, my love,’ said Mr. Micawber.

‘Pray, my dear, allow me to conclude. Here is Mr. Micawber, with a variety of qualifications, with great talent–I should say, with genius, but that may be the partiality of a wife–‘

Traddles and I both murmured ‘No.’

‘And here is Mr. Micawber without any suitable position or employment. Where does that responsibility rest? Clearly on society. Then I would make a fact so disgraceful known, and boldly challenge society to set it right. It appears to me, my dear Mr. Copperfield,’ said Mrs. Micawber, forcibly, ‘that what Mr. Micawber has to do, is to throw down the gauntlet to society, and say, in effect, “Show me who will take that up. Let the party immediately step forward.”‘

I ventured to ask Mrs. Micawber how this was to be done.

‘By advertising,’ said Mrs. Micawber, ‘in all the papers. It appears to me, that what Mr. Micawber has to do, in justice to himself, in justice to his family, and I will even go so far as to say in justice to society, by which he has been hitherto overlooked, is to advertise in all the papers; to describe himself plainly as so-and-so, with such and such qualifications and to put it thus: “Now employ me, on remunerative terms, and address, post-paid, to W. M., Post Office, Camden Town.”‘

….’I feel that the time is arrived[, continued Mrs. Micawber, ‘]when Mr. Micawber should exert himself and–I will add–assert himself, and it appears to me that these are the means. I am aware that I am merely a female, and that a masculine judgement is usually considered more competent to the discussion of such questions; still I must not forget that, when I lived at home with my papa and mama, my papa was in the habit of saying, “Emma’s form is fragile, but her grasp of a subject is inferior to none.” That my papa was too partial, I well know; but that he was an observer of character in some degree, my duty and my reason equally forbid me to doubt.’

….Our conversation, afterwards, took a more worldly turn; Mr. Micawber telling us that he found Camden Town inconvenient, and that the first thing he contemplated doing, when the advertisement should have been the cause of something satisfactory turning up, was to move. He mentioned a terrace at the western end of Oxford Street, fronting Hyde Park, on which he had always had his eye, but which he did not expect to attain immediately, as it would require a large establishment. There would probably be an interval, he explained, in which he should content himself with the upper part of a house, over some respectable place of business–say in Piccadilly–which would be a cheerful situation for Mrs. Micawber; and where, by throwing out a bow-window, or carrying up the roof another story, or making some little alteration of that sort, they might live, comfortably and reputably, for a few years. Whatever was reserved for him, he expressly said, or wherever his abode might be, we might rely on this–there would always be a room for Traddles, and a knife and fork for me. We acknowledged his kindness; and he begged us to forgive his having launched into these practical and business-like details, and to excuse it as natural in one who was making entirely new arrangements in life.

If you want to see the site, just email me for the link.

Three young men in a small pickup with had just disposed of an old carpet when I got out of the car. The driver looked at my load and then asked the attendant, “What are the rules about asking other people for their junk?”

Three young men in a small pickup with had just disposed of an old carpet when I got out of the car. The driver looked at my load and then asked the attendant, “What are the rules about asking other people for their junk?”

M’s sister knew just the ticket for such an evening: burgers from

M’s sister knew just the ticket for such an evening: burgers from  “Four,” the man intercepted the waitress, not looking at us.

“Four,” the man intercepted the waitress, not looking at us.